Gavriel D. Rosenfeld's The World Hitler Never Made: Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism, published this year (June 2, 2005) by Cambridge University Press, contains an analysis of Richard Grayson's "With Hitler in New York" appears on pages 234-236:

Several years later, [Michel] Choquette’s tale ["Stranger in Paradise"] was itself surpassed by the most normalized of the decade’s narratives – American writer Richard Grayson’s 1979 short story, “With Hitler in New York.” Set in an indeterminate year, Grayson’s work recounts an unnamed narrator’s several days of socializing, partying and walking the streets of New York with Adolf Hitler. The Hitler described by the narrator is a contemporary Everyman, indistinguishable from others of his generation. A tall, dark and handsome individual who wears a leather jacket, Hitler is quick-witted, gregarious and popular. Nothing of much importance happens in the story, which is more a chronicle of banal events than a sustained plot. Its most intriguing aspect, indeed, is its vagueness regarding whether the Hitler in the story is in fact the “real” Hitler or simply another man coincidentally possessing the same name. By the end of the tale it is clear that the man is, indeed, the (allo)historical Hitler. The hostile reactions toward him by other characters in the story show that he continues to suffer from a sullied reputation due to unspecified historical misdeeds. The mother of Hitler’s girlfriend, Ellen, dislikes him and will not speak to him; a patron in a coffee house “recognizes Hitler [but] everything is too mellow for him to make a scene.” Yet Hitler’s negative image is complicated by the fact that his girlfriend is Jewish and he enjoys strolling around Brighton Beach listening to elderly Jews sing old Yiddish folk songs. The historical significance of this allohistorical Hitler remains ambiguous. The narrator’s drunken observation at a party that Hitler deserves to win the Nobel Peace prize is as cryptic as his concluding question to him whether he “ever feels bitter.” Hitler’s cryptic response – that he feels “useless” – suggests some kind of grand past that has given way to a banal present, but nothing more.

Grayson’s portrayal of Hitler’s survival in an alternate New York City, like Choquette’s, was notable for its complete abandonment of a morally grounded framework. Unlike the tales of [Brian] Aldiss, [George] Steiner, and [Pierre] Boulle, which still depicted him as unrepentant for his crimes, Grayson’s story left unspecified which historical misdeeds he may have committed – or whether he committed any at all. Without a clear criminal background to be held accountable for, Grayson’s Führer is no fugitive but merely another human being who blends into the crowd in New York City. And yet it would be a mistake to see Grayson’s humanization of Hitler as an act of rehabilitation. Rather, Grayson’s tale imagines an alternate world that has largely forgiven Hitler for his crimes and forgotten them. Such a world – in which the narrator can ignore his grandfather’s own death to get stoned with Hitler and can muse, “I wonder if I am beginning to fall in love with him” – is a callous, unfeeling one, in which historical consciousness has either atrophied completely or become irrelevant to most human beings. In short, it is a nightmarish world of total amnesia. In all probability, this is the primary point Grayson was looking to make. Evidence for this reading is provided at the very end of the autobiographical introduction to With Hitler in New York (which immediately precedes the story by the same name) where he describes his adolescent withdrawal from his family and concludes “I just lay in my bed trying to sleep. When I slept I had nightmares.” Given this de facto premise to the short story “With Hitler in New York,” Grayson’s account of a world in which Hitler hardly differed from anyone else was meant to be seen as a bad dream.

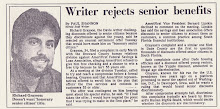

In offering this conclusion, Grayson’s story can be taken as a complex response to the Hitler Wave. Like Boulle and Choquette, Grayson was strongly influenced by the Hitler Wave’s de-demonization of the Führer and drafted the most humanized portrait of him yet to appear in postwar alternate history. Yet Grayson was also concerned about, and tried to counteract, the Hitler Wave’s progressive normalization of the deceased dictator. As a writer of Jewish background who grew up around Holocaust survivors in Brooklyn, Grayson was concerned by the increasing fascination with Hitler and aimed to show, in reductio ad absurdum fashion, its dangerous endpoint – a Hitler who was regarded as any other human being. The author’s decision not to bring Hitler to justice in “With Hitler in New York,” then was animated by different aims from those that shaped the tales of Aldiss, [Gary] Goss, Steiner, Boulle, and Choquette. For while these narratives were less overly committed to remember the Nazi past for its own sake, Grayson’s story was intended as a plea not to forget the Nazi past for its historically specific horrors. Still, in effect, “With Hitler in New York” did not differ substantially from these tales insofar as it, too, dramatically challenged the limits of representing Hitler and offered a radically altered portrait of him as a “regular guy.”

Taken together, the tales of Aldiss, Fadiman, Goss, Steiner, Boulle, Choquette, and Grayson all reflected the broader phenomenon of normalization. This was most obvious in their de-demonization of Hitler as a character. The fact that, in nearly all of the narratives, Hitler’s enduring capacity for evil was overshadowed by his average human traits represented an increasing willingness, in the wake of the Hitler Wave, to view the Führer in non-judgmental terms. The motives underlying many of these narratives also reflected an increasingly normalized view of the Nazi past. These writers showed Hitler evading justice in order to offer universal conclusions about the human condition – most of them pointing to the continued existence of contemporary political crises. For all of their moral evidence on liberal-left politics, however, the effect of their tales was to divert popular attention from Nazism as a specific historical phenomenon.