The Washington, D.C.-based literary magazine Gargoyle reviews Richard Grayson’s Eating at Arby’s in issue 22/23 (1983):

___________________________________________

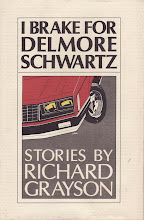

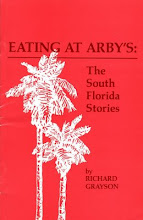

Eating at Arby’s: The South Florida Stories,

by Richard Grayson, Grinning Idiot Press,

P.O. Box 1577, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11202,

1982, 24 pp., $3, saddle-stitched.

___________________________________________

In this short collection, Richard Grayson has found a style of daffy unreality to make his experience of anomie in South Florida. In one-page vignettes, he writes of such diverse subjects as Haitian refugees, Cubans, Blacks, gays, “crackers,” old people, and the proliferation of malls, guns and Colombian dope through the eyes of a Looney Tunes duo, Manny and Zelda. They and their friends talk in Dick and Jane sentences about these subjects. Always they react with zany blankness, sometimes with hilarious “logic,” as in this example:

“Guns can be fun,” said José. “Guns can be fun and help you if you own a clothing store like I do . . . Guns can be your friends.”

“It is important to have friends here in South Florida,” said Zelda. “Manny, I want to shoot that gun. That gun will become our friend, just like José is our friend.”

“Nuestro amigo,” Manny said, as José handed him the gun.

Some pieces zing, as “A Long Boat Ride,” in which Manny mistakes Haitian refugees for newly arrived tourists. Correcting him, Zelda says:

“Soon they will be happy. . . Now that they are in South Florida, they will be very happy."

“Everyone is happy here,” said Manny. “. . . Let’s make friends with those Haitian refugees. Let’s take them with us to eat brunch at the Rascal House.”

“Oh Manny!” cried Zelda. “You are so silly. Haitian refugees do not come here to eat brunch at the Rascal House. They come here for freedom. You cannot get freedom at brunch at the Rascal House.”

Other piece deliberately court banality, as in “At the Beach,” where Chip says:

“. . . It is beautiful here. . . My gay friends and I like it very much. We have fun here. People are nice. The weather is good. We can enjoy the beach and make friends.”

The repetitious style of first-grade primers is surreal; its deliberate flattening suggests vacancy, diminution. Words like “nice,” “happy,” “fun,” clone themselves with dizzy inarticulateness. The satirist’s spleen, though clearly present, is muted. The grand style as in Swift is here deliberately monochrome and reductionist. There’s a buttoned-down quality, a muffling, even evisceration of content in places. Grayson’s too hip, maybe too pessimistic, to breastbeat. For his method, he appears to have taken literally, for humorous effect, a quotation from Emerson:

“Do not craze yourself with thinking, but go about your business. . . Life is not intellectual or critical, but sturdy. Its chief good is for well-mixed people who can enjoy what they find without question.”

And of course Zelda and Manny do just that. The vacation mentality, the weather, the wardrobe choices (“I like to see people wearing pink pants and white shoes”)—all point to a dreamland emptiness gussied up—or down, in Graysonstyle—as if for the Saturday morning cartoon crowd. It’s a method of despair.

Grayson’s deliberate lightness, though, is flawed by the final “Some Sad News,” where we learn José has been murdered. Though “murder is not fun”—virtually the only thing Manny and Zelda say isn’t fun in South Florida—the heavy-handedness spoils the Disneyland feeling. I would have preferred to have the collection end with the wonderful “A Chanukah Party.” A skewed United Nations gathers at Manny and Zelda’s: Bob the bisexual (who says he’s not bilingual), José the Cuban, Chip the gay, gramps and grandma, and Lois, the black chiropractor from Liberty City who wears Sasson jeans. Lois brings Hassan, her Palestinian friend, to the Chanukah party. Zelda says:

“You will be our Palestinian pal, too.”

“Thank you, Zelda,” said Hassan. “I will be glad to be your pal. I like your Sasson jeans and the food you have brought in from Arby’s.”

Zelda smiled. “In South Florida we are all friends. We are lucky to be here. We have malls and condos and happy, friendly people.”

“I love it here in South Florida,” said Manny. “Every day is like a Chanukah party here.”

Much current writing is decidedly casual. Big deals are out. This is an age of burnout. Grayson follows this trend here with his stylish vacancy, his deadpan blankness. Moreover, the discontinuities that flourished in her earlier fiction are tethered down here. Eating at Arby’s is a seamless collection of virtually the same encounter repeated eighteen times—the two innocents making happy-face babble as if they’re playing dolls. (Maybe the repetition of the encounter itself is a discontinuity, one which suggests hopeless stall.) Reading this collection is a little like finding Clark Kent when you’d hoped for Superman. Eating at Arby’s goes down easy: it entertains, it disturbs, but not too much. It’s a little like a sitcom, where the same joke gets repeated week after week. You like it but you look around uneasily and say, is this all?

—Maryl Jo Fox