The American Book Review reviews I BRAKE FOR DELMORE SCHWARTZ, DISJOINTED FICTIONS,EATING AT ARBY'S on pages 21-22 of its November/December 1984 issue:

From Our House to Bathos

* * *

I BRAKE FOR DELMORE SCHWARTZ

Richard Grayson

Zephyr Press

13 Robinson Street

Somerville, MA 02145

1983, 95 pages

Cloth, $9.95; Paper, $4.95

EATING AT ARBY'S: The South Florida Stories

Richard Grayson

Grinning Idiot Press

P.O. Box 1577

Brooklyn, NY 11202

1982, 24 pages

Paper, $3.00

DISJOINTED FICTIONS

Richard Grayson

Cumberland Journal

P.O. Box 2648

Harrisburg, PA 17105

1981, 64 pages

Paper, $3.00

Reviewed by Jaimy Gordon

_________________________

Eating at Arby's and Disjointed Fictions clamor for laughs before one even opens the covers. True, I Brake for Delmore Schwartz is a dignified volume, except for the title and the enclosed red bumper sticker that spells it out in large letters. But the flamingo-pink cover of Eating at Arby's announces that Richard Grayson ran for Town Council lately in Davie, Florida, with a campaign promise to give horses the vote; and the back of Disjointed Fictions reports that he was once a candidate for the Democratic Vice-Presidential nomination. Both books offer columns of testimonials on Grayson's work, some from trade organs like Publishers Weekly, others from Florida community rags like the Delray Beach News Journal and the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel. These critics are, on the whole, somewhat puzzled by Grayson—a woman from the New York Post hopes that "his literary career may be blessedly brief"—but most know a joke when they see it. They invoke Steve Martin, Saturday Night Live and the muse of stand-up comedy to explain Grayson, though a certain uneasiness lingers between the blurbs: If this is Saturday Night Live, can it be literature?

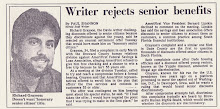

And now a second clipping from the Miami Herald slips out of Eating at Arby's, hinting at yet another South Florida story. In October, 1982, an alert reporter sniffed out a small scandal behind the chapbook: Richard Grayson employed a $3000 grant from the Florida Arts Council to chronicle the banal adventures of Manny and Zelda among mall shoppers, Marielitos, and drug murderers, in flat, repetitive, Dick and Jane-style prose. The reporter finds Grayson in his English Department cubicle at Broward Community College, and he does not allow her to go away disappointed. He elaborates on his municipal campaign platform: besides enfranchising horses, he was in favor of giving tactical nuclear weapons to the Davie police force. He threatens to sell the book on the street and says of the Florida Arts Council: "I'm sure they'll be delighted to see such a great piece of literature came from their money." But he adds a typical disclaimer: he is grading well over a hundred "illiterate papers" a week. "As you can see from the book," he tells her, "it doesn't do much for your writing style."

The willingness to be a public clown—or, more accurately, to present the appearance of a wistful nobody scribbling away in private who occasionally bursts out as a farcical publicist, exposing himself before the world—continues unabated inside Grayson's prolific but never prolix fictions. The several strains of his humor occur in more or less varied combinations according to the story, and I much prefer those loosely segmented chains of association in the first person (happily, two thirds of the stories in both Disjointed Fictions and I Brake for Delmore Schwartz fall into this category), where all his mannerisms exist side by side, to his more symmetrical and abstract pieces; for, in the absence of the first person, Grayson's prose loses much of its charm and is shown to be a rather blunt and inelastic tool. Grayson is not a graceful stylist, and as soon as the expression of a personality (or the illusion of this) disappears, his inventions and satires move on leaden feet. This is particularly true of Eating at Arby's, whose conceptual plan may sound comic, but which, as a literary experience—that is, as something to read—is all but insufferable. Manny and Zelda speak the same stiff, uncontracted idiom with which Dick and Jane stupefied us in second grade; the tiny vocabulary of their dialogues expands primer-style from a base of I like/nice/fun/friends/important/good/glad/ happy/man, to include "gay," "I-95" and "accidents"; "Century Village" and "Arby's"; "trip to Colombia"; "sore back" and "chiropractor"; "hurricane," "cocaine," "gun," and "murder." Besides offering a draught of gall to the Arts Council, the little book has two virtues, of a sort; it does not take a subtle intellect to feel the point of its satire, so that Grayson's contempt, which almost any dolt can share, is ultimately reassuring; and it is all over in twenty-four pages.

The variegated texture of the first-person narratives that most engage his admirers and baffle his critics is challenging to describe, since it is through juxtaposition that these deliberately unshapely tales achieve their effects. There is a strain of soap-opera exhibitionism in Grayson; sown through I Brake for Delmore Schwartz are revelations of an embarrassingly personal nature, often maudlin, often clearly untrue: "At this time I was suffering from schizophrenia," he says in passing, in "Is This Useful? Is This Boring?." "No matter how hard I tried, I never could take the whole bottle of sleeping pills," he says in "Oh Khrushchev, My Khrushchev." "But maybe for Khrushchev I could do it." A commonplace East Coast Jewish extended family, divided between New York and Miami and subject to cancer and bar mitzvahs, is put to use in many of Grayson's stories, variously as the basis of anecdotes that would not go over badly on the borscht circuit ("little antidotes," the grandfather in "Nice Weather, Aren't We?" calls them) or for highly suspect pathos. In one story in I Brake for Delmore Schwartz, the narrator's sister has drowned; in another, leukemia has snatched her away; in Disjointed Fictions ("Escape from the Planet of the Humanoids"), a sister is still tirelessly dying; the reader is instructed to "Feel this:"

The pain of frustration that a man feels when he is trying to write a sentence about how a character feels at his sister's funeral and can only come up with this fragment: Better her than me.

But in another tale the sister's phone number ("FOR A GOOD LAY CALL 969-9970") appears on a subway map in the IRT; and in yet another, she's alive and prospering as Roslyn, "now a Long Island dermatologist and mother of twins," who says, "Yes, I remember Saulie's bar mitzvah. . ."

The thread of the pathetic family saga intertwines with another characteristic one that I will call the lament of the schlemiel in the creative writing workshop. He is no longer in it, of course, but it has left its mark. The narrator worries about the quality of his fictions, checking them against mumble-mouthed platitudes of the craft; and these are travestied evenhandedly whether they arise from the post-modernist school or the Famous Writers' School. Grayson has an MFA from Brooklyn College, so he knows the rhetoric. In "Is This Useful? Is It Boring?," the narrator boasts, "For two years I studied Fiction Writing in one of the best universities in the country. . . .We were supposed to write new kinds of fiction. One writer called himself a 'post-contemporary' writer. That says it all." But from this self-congratulatory beginning, the voice disintegrates into a muddle of pomposity and self-pity: as a writer who misrepresents people as characters and otherwise can "get away with murder," the narrator is "a pretty powerful person"; well, no, he says, actually he writes out of a neurotic need for attention; in fact, he writes to get revenge on some Italian kids who once called him "Irving"; then the narrator changes his mind — "I can't even find the right words" — maybe he didn't learn anything in college after all. So much for the tenets of the experimentalists.

But then there are the traditionalists to contend with. Halfway through "Nice Weather, Aren't We?," the narrator's girlfriend Rosalie sneaks in "while I was out getting a Fresca" and writes "NO FOCUS" on the middle of the page. "Criticism like that I don't feel useful," he says huffily. But he admits it's all a strain. In "The Four Faces of Freud":

Listen, there is no point in finishing this story... I can't understand why some editor would print this, except as a cry for help. I am mentally ill.

This is the Grayson manner in endless variations: alternate strains of impudent posturing that breaks down in self-parody, equally disingenuous confessions of the writer's ineptitude; and, withal, punchlines and puns that he will labor for many paragraphs to set up, like, "I never promised you a prose artist," and, "Fiction's no stranger than Ruth." All these parts are suffused with the appealing professional anxiety of a small-time writer scrabbling against odds and without much concern for his dignity to get a little renown for himself. Grayson once said in an interview (Gargoyle 17/18) that he keeps his fiction short because "fragmented, self-conscious novels might very well be boring. Some people say that fragmented, self-conscious stories are also boring, but at least they're short."

It seems worth noting that Grayson perceives his readership, so far, more clearly than his readership perceives him. There is a sound precedent for that loose-jointedness of his fictions that so confounds his critics, a venerable one that reaches back far beyond the mimetic and novelistic bias that is in fact a middle-class parvenu in the world of letters. It is the satiric tradition of Erasmus and Rabelais, of Diderot, of Swift and Sterne and Peacock, and one may find this tradition, as in Grayson, the shape of a miscellany founded on a loose association of ideas, frequently with humble apologies from the author; idiosyncratic asides, digressions, and non sequiturs; catalogues and inventories; structures of information borrowed from extra-literary domains of the language; dialogues, patterns of query and response, and other instances of the unexpected, the undignified, the fitful, the intellectually pretentious breaking down into parody. But the brevity of Grayson's fictions is his own design, based on a just though severe estimate of the attention span of a literary peer group he understands all too well. In the same interview, Grayson told his questioner, "Actually, if you look at my work, it's probably more influenced by TV than by literature." Grayson writes for (because he is one of) a literati that watches TV, that is hounded by the neologisms "writers' workshop," "Citibank," and "co-op apartment." The narrator of "I Brake for Delmore Schwartz" walks the streets of New York, Citicard in hand—the same streets trod by Isaac Bashevis Singer and by the shade of the departed Schwartz—asking himself if it wouldn't be smarter to take a course in computers for a guaranteed fourteen grand a year, than to persist in this thankless manner of living.

Perhaps the most confusion about whether to place Grayson in the contemporary literary scheme is owing to the imperfect self-knowledge of that public of which Richard Grayson is the jester. We — and I mean you and I — live in a strange literary economy where most writers between the ages of twenty-five and forty accept the lot of the sort-of-published, the semi-solvent, the great unread, against the backdrop of an age of media super-celebrities; so that we are unable to escape the evidence of our under-appreciation though fully aware of the ludicrousness of the contrary. Richard Grayson constructs a literary persona out of just this predicament. He is a satirist and parodist so timely that his brothers and sisters may not yet discern themselves in his mirror. Certainly our hapless group that writes and studies writing and cogitates about writing but cannot know its audience deserves its own comedian, if it can learn — as Richard Grayson has — to laugh at itself.

_________________________________________________

Jaimy Gordon is the author of Shamp of the City-Solo (Treacle Press) and Circumspections from an Equestrian Statue (Burning Deck), among other works. She presently teaches at Western Michigan University.