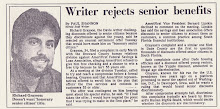

The St. Petersburg Times reviews Richard Grayson’s I Brake for Delmore Schwartz on Sunday, September 4, 1983:

Self-conscious writer draws strength from humor

___________________________________________

I Brake for Delmore Schwartz

By RICHARD GRAYSON

Zephyr Press, $9.95, hardcover; $4.95 paper

Reviewed by SANDRA THOMPSON

___________________________________________

Richard Grayson, author of I Brake for Delmore Schwartz, a collection of fifteen short stories with such unlikely titles as “Nice Weather, Aren’t We?” “Is This Useful? Is This Boring?” and “Oh Khrushchev, My Khrushchev,” is a displaced New Yorker who has been teaching and writing on Florida’s East Coast for the past two years.

A word of warning: Grayson is a self-conscious writer who enters into direct dialogue with his readers—that means you—but in a much different way than Henry Fielding did in his “Dear Reader” passages in Tom Jones. Times have changed since our first novelistic fiction, and Grayson will be the first to tell you so.

He begins “Nice Weather, Aren’t We?” with “You really want to read this?” Two pages later, the narrator says, “Do you realize that since the beginning of this story, about a hundred people have died? In real life, I mean.” Then he talks about a fellow student in one of his writing classes, whom he calls “Ruth.” He hates Ruth because she never changes the names of the characters in her stories. Then we learn that the fictional “Ruth” is actually real-life “Bruce,” but the narrator changes his name to Ruth for purposes of the story, especially citing his line, “Fiction’s no stranger than Ruth.” If he had said, “Fiction’s no stranger than Bruce,” he points out, “It wouldn’t have had half the impact. And I’m not sure how much impact it had.”

THEN, he tells the reader that while he was writing that, Bruce walked in—and slugged him.

Seemingly without shame, Grayson commits what some writers consider to be a professional sin: writing about writers. He even writes about a relatively new and controversial phenomenon among contemporary American writers: university creative writing program. I know from where Grayson speaks, because I am a graduate of a university creative writing program; in fact, the same university creative writing program as Grayson. Which doesn’t mean Richard Grayson is a friend of mine—that’s not why I’m writing this review. Actually, I hardly know the guy. (This is the kind of inside info Grayson gives you in his stories.) He tells us about one creative writing professor who calls himself a “post-contemporary writer” and another who teaches him that “every story must have a beginning, a middle, and an end—‘preferably not in that order.’”

Clearly, the meaning an value of contemporary fiction intrigue Grayson. In “Nice Weather, Aren’t We?” the narrator tells us, “I only write true stories. I used to be an editor at a big publishing house in New York and every day manuscripts would arrive. . . accompanied by cover letters like the following ‘Dear Sir: I am presenting a novel about a Turkish princess who became a gunfighter and a sheriff in the Old West to protect her Christian Arab people from the hostility of the Anglo-American outlaws during the days of the cattle boom after the Civil War. . .”

Grayson concludes, “They ought to give the electric chair to whoever tells people that ‘everybody’s got one good novel in them.’”

GRAYSON TAKES some chances. For instance, I can’t think of any other writer who has written in the voice of a germ—as Grayson does in “The Autobiography of William Henry Harrison’s Cold,” in which the cold sees itself as a presidential assassin.

Grayson’s great strength is his humor, and his best stories are the ones that stop a laugh short of heartbreak. “Slightly Higher in Canada” begins with this sentence: “When my aunt called to say that my father had gone to England to get married to some little tramp, I was the one to tell my mother.” The next morning their mother doesn’t wake up; after she does, the narrator and his sister take her to stay with her parents in a retirement community outside Fort Lauderdale. The mother sits out in the sun with her straps lowered, the grandfather plays poker, and the grandmother fixes starchy meals. “Altogether we were down there three months. Over the television they would always tell us the weather up North was bad. Sometimes people came down from the North and they would say the weather wasn’t all that bad, but nobody in the condominium would believe them.

So things go until this line: “After my sister drowned I didn’t think much about it until my father came to Florida with his new wife.” The narrator starts fooling around with drugs, getting high, and “seeing girls who looked like my sister from the back” until his grandfather tells him to go away. He does, to Canada—hence the title of the story.

In “Reluctance,” a young boy is told by his great-grandmother that if he doesn’t wash his fingers “the Germans will get all over them. She said then the Germans would take over my whole body, and then when I was sleeping the Germans could take over my parents’ bodies, and finally the Germans could take over her own oh so large body. . . I did not want that, so I washed.” This very short story—it’s only two and a half pages—telegraphs to us in strong prose the story of this boy’s childhood. The ending brings us up short with his adult reality.

And in “Hold Me,” while the narrator is trying to explain the New Math to his sister, his father comes into the room, crying, and tells them he can’t live with them anymore. At the end of the story, the narrator, now an adult, calls a radio talk show, saying he wants to talk about sending troops to Zaire—but what he actually says is more immediate, more personal, and sad.

Actually—and now I’m telling the truth—I was lying when I said I hardly know Richard Grayson. After reading this collection of stories, I think I know him pretty well. So will you.

SANDRA THOMPSON

______________________________________

The author is a reporter for the Floridian section of the St. Petersburg Times. She has been a contributor to numerous magazines and is the winner of the 1982 Flannery O'Connor Award for Short Fiction.