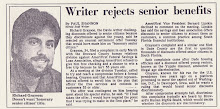

The American Book Review has a joint review of Richard Grayson's I Survived Caracas Traffic and Jonis Agee's A .38 Special and a Broken Heart in its April/May 1996 issue:

_________________________________

Irony and/or Authenticity

_________________________________

A .38 Special and a Broken Heart

Jonis Agee

Coffee House Press, 27 N. 4th St., Minneapolis, MN 55401; 130 pages; paper, $10.95

__________________________________

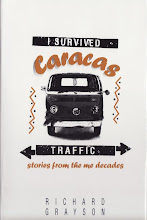

I Survived Caracas Traffic: Stories from the Me Decade

Richard Grayson

Avisson Press, 3007 Taliaferro Rd., Greensboro, NC 27408; 144 pages; cloth, $21.00

__________________________________

Tyrus Miller

FOR today’s storyteller, irony is less a chosen mode, a figure of speech, than an atmosphere which one breathes of necessity, whether or not the surrounding air smells sweet. Starting from this recognition of irony as a kind of fated climate, the best Anglo-American short fiction writers of this century, from Joyce, West, and Barnes to Carter, Creeley, Davenport, and Abish, have explored ways to understand and inhabit an ironic literary cosmos, without either denying its existence or being consumed by it. It is fitting, then, that in reading new works of short fiction one measures them against the standards set by the masters of the genre in coming to grips with the problem of irony.

. . . .

Richard Grayson's collection I Survived Caracas Traffic is nearly the antipode of Agee's collection: cynical, comic-satiric, resolutely urban "East Coast." Grayson's book assembles twelve previously published pieces of magazine fiction. The topical references in the stories suggest, in fact, that the collection includes work from some time along, along with more polished recent work. For example, one story mentions "People's [sic] Express," the now-defunct Newark-based cut-rate open-seating airline: I pick up a strong aroma of 1984 or 1985 in this story. The risk of such immediate incorporation of topical detail is, of course, that it may lose its charge or even its meaning as time goes by. I can remember a lot of joking about People's [sic] Express about ten years ago, but now one would be lucky to find an audience who even remembers what it was.

Grayson's talents show themselves most fully with his swiftly drawn characters, rendering them in sharp paradoxical sentences. These character appear like walking non sequiturs. In fact, one of the most successful pieces in the book, "Mini-People," is a concatenation of these character sketches:

Dr. Bender has two daughters by his first wife. They call him up during his sessions with his patients and ask for help with their homework. When Dr. Bender cannot help them, he sometimes asks the patient who is with him to do so. Gail helped Dr. Bender's daughter do a report on off-track betting.

Dr. Bender is very much a male chauvinist. He says he is a phallic imperialist. He thinks this is very funny. ("Mini-People")

Grayson's limitations reveal themselves just as quickly, however, whenever he has to narrate anything. Exposition, the communication of background information in order to set up the story, seems to give him particular trouble. In other cases, he lets significant details fall from the narrator's mouth like a bolus of partly-chewed meat: "Some things I couldn't bring myself to talk about with Sean. Like his father ("I Survived Caracas Traffic"). The reader sits in suspense wondering just what the author is about to reveal about Sean's father! Obligingly, the author fills us in with his next paragraph: "At first I figured his parents were divorced, but when he talked about getting social security, I realized Sean's father had died, and from other things he said -- though he never mentioned his father -- I realized it was a hurt so deep I didn't dare explore it." That pretty much covers all we need to know about Sean's father, so we can move on to other things.

One story, entitled "A Clumsy Story," lays bare the mechanisms of short story writing. The "clumsy story" which is the internal object of the framing author's "Preface" and "Apology" bears an uncanny resemblance of style and character of other stories in the book. In a preemptive gesture of meta-fictional irony, thus, Grayson takes up criticisms of his work (such as the one I made above) and incorporates them as the premise of a new story. The question arises within the reader's head: Is Grayson a more proficient writer than I had thought? Maybe all those awkward passages were a sign of true sophistication! Yet it is not just the framed story that is clumsy; it is also the meta-fictional handling. There is none of the comic inventiveness of Barth or Sorrentino; nor is there the poetic play with narrative time that one finds in Calvino or Cortazar.

Yet still one last lingering doubt remains: perhaps this clumsy meta-fictionalizing is an even more subtl ironic criticism of the pretense of meta-fiction to refresh the text, to save it from its fall into conventionality. Perhaps Grayson is telling us that meta-fiction itself has become convention, that this war-horse of "post-modern fiction" is as flyblown as the conventions of Victorian realism. Perhaps. But may I be forgiven if I express my doubt that this is the case. The problem with irony, of course, as Schlegel had already noted nearly two hundred years ago, is that there is no sure way of telling where it begins and ends Irony tends to spread over everything it touches, whether by design or by unwanted extension. But as another man wisely said, just because I can't prove that an abyss won't gape before me when I open my door, doesn't mean I need to act as if it will. Accordingly, then, I draw this review to its meeted close with a timid profession of faith: sometimes "a clumsy story" is just that, and meta-fictional irony -- or is it meta-meta-fictional irony? -- can do nothing to persuade me that it is more

Tyrus Miller teaches Comparative Literature, English and Film Studies at Yale University, where he is working on a critical study of late modernist fiction. His most recent publications include articles on Beckett, Mina Loy, William Carlos Williams, C. Day Lewis, John Cage, and Massimo Cacciari.