skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Here is the post from

Richard Grayson's MySpace blog for Sundary, September 30, 2007:

On Saturday at 4 p.m. I was one of about a hundred people seated in the spanking-new auditorium of the Dr. S. Stevan Dweck Center for Contemporary Culture at the Grand Army Plaza Central Library to hear a riveting lecture, "The History and Future of Brooklyn," by Mike Wallace, a distinguished professor of history at CUNY, chair of the Gotham Center for New York History and co-author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898.

Wallace discussed Brooklyn's past and future in terms of three currents in the river of history: Brooklyn's relationship with Manhattan, its macroeconomic base, and the demographic flows in and out of the borough.

As a colonial city, Brooklyn's role was to feed the profit centers of the British empire, the sugar plantations of the Caribbean whose land was too valuable to use for crops to feed the slaves who worked there.

Primarily agricultural hinterlands, Brooklyn also served as the port to send food and other supplies – some manufactured here – to the West Indies and in return to get sugar and rum. (That explains why the Havemeyers' Domino's Sugar and Revere Sugar built huge operations in Williamsburg and Red Hook.) Back then, Brooklyn's population was largely Dutch, English and African; slavery was widespread.

American independence cut off this trade and was an economic catastrophe until Brooklyn found new trading partners in the Spanish Caribbean, primarily Cuba and Puerto Rico. As the Erie Canal opened up New York's access to the agricultural Midwest, Brooklyn's farms were replaced by major manufacturing, with ironworks and furniture factories.

The industrial revolution eventually brought renewed trade with England, which got much of the cotton for its textile factories from the American South via ships from the port of Brooklyn. The port boomed, and around the same time, Brooklyn Heights became America's first suburb, a bucolic alternative to overcrowded Manhattan.

When Manhattan became the financial, entertainment and media capital of the nation, skyscraper office buildings proved more profitable than factories there, so manufacturers moved to Brooklyn with facilities like the innovative Bush Terminal, joining manufacturers with the port via its railway.

As Brooklyn became a major producer of beer and baked goods, it also served as home to a world-class resort, Coney Island, as well as baseball stadiums, movie palaces, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Prospect Park, the museum and other venues for industrial age leisure.

Brooklyn capitulated, Wallace said, to the 1898 annexation into Greater New York because it needed access to Manhattan money and its water supply.

By the start of the 20th century, a great demographic shift occurred as Jews, Italians, Norwegians, Syrians and other ethnic groups flowed across the new bridges into Brooklyn; Fort Greene and Bedford-Stuyvesant become magnets for African-Americans from the South; Puerto Ricans, U.S. citizens after 1898's other big event, the Spanish-American War, also move into the borough in large numbers; and Brooklyn's southern farms are broken up into suburban subdivisions, some as posh as Prospect Park South.

Foreign immigration is largely stopped by 1924's restrictive, xenophobic law – opposed by young Brooklyn Congressman Emanuel Celler, who, as House Judiciary Chairman in 1965, would push through the relaxed immigration act that led to the waves of newcomers from all over the world, replacing older residents who fled the borough for the suburbs and Sun Belt.

Wallace discussed Brooklyn's important role in World War II and then its slow decline and deindustrialization as thousands of manufacturing jobs disappeared. Most of the older crowd in the audience, including myself, remember the nadir of the 1970s.

I can recall a primary challenger to the seeming borough-president-for-life plastering Brooklyn with posters that read "Abe Stark, We Love You – BUT BROOKLYN IS DYING!" He didn't win but nearly all of us agreed with his sentiments.

The "turnaround" of the 1980s with renewed gentrification was really very small-scale, Wallace said; for a good part of Brooklyn, the key economic engine was actually the illegal crack trade.

Unemployment surpassed 10% as late as the early 1990s; AIDS and TB rates rose 700% in parts of Brooklyn; the old ethnic rivalries among Jews, Irish, Italians and Germans disappeared as they all became "white" and the new tensions were racial.

Wallace reminded the audience of the racial tensions of the era, from the 1968 teachers' strike – we old-timers recall the name of Rhody McCoy, the most well-known Brooklynite of the day (he was head of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville school district) – to the 1991 Crown Heights disturbances and the racially-charged Bensonhurst murder of Yusuf Hawkins.

Brooklyn's recent revival is the result of the same forces that have always shaped its history, Wallace said: its relationship with Manhattan (as those who could no longer afford to live there moved across the river as gentrifiers), and more importantly, the foreign immigration which has brought the world here – so much so that Brooklyn is now the third largest Ecuadorean city in the world, after Quito and Guyaquil.

Wallace ended his talk by showing a variety of maps of Brooklyn's changed demographics. Especially interesting was a map of census tracts showing which groups dominated each little neighborhood, with many an amalgam like "black-white" or "Hispanic-Asian."

This map showed how the city's third large Chinese neighborhood is developing as Hispanic residents push Asians south of Sunset Park into Bensonhurst as Russians move east from Brighton Beach, setting up the Chinese-Russian "frontier" I've noticed by the signs when I take the bus along 86 Street.

What happened to the Italian-American Bensonhurst of my youth, depicted in "Saturday Night Fever"? Essentially, Wallace said, though it still exists, the Italian community has "aged out" and is leaving the area one way or another.

Wallace mentioned how along Ocean Parkway, the Syrian Jewish community lives alongside Muslims from Pakistan and Bangladesh; how Brooklyn's Mexican residents have formed councils not just to send money to their home cities but to have a role in how it is spent; how former all-white communities like Canarsie and adjacent areas like my old block are now largely black (mostly West Indian).

Given these "amazing juxtapositions" and that today's immigrant communities, unlike those of the past, are still very involved in their native countries, Wallace said that some may think it is odd that somehow World War IV has not broken out in the borough.

A map and chart showed that at least one Brooklyn community seems to have no dominant group and is roughly one-quarter white, Asian, black and Hispanic. That's Ditmas Park ("Yay!" cheered the old ladies in front of me) – and surprisingly, it's not the border of adjacent ethnic communities, just a place where everyone seems to be content living side by side.

Is this too good to be true? Wallace asked. We will see if the subprime woes and the faltering financial markets – in evidence in Brooklyn by Wallace's ominous map of rising foreclosures in the borough (anyone on the Church Avenue bus in East Flatbush will notice "Avoid Foreclosure!" signs posted everywhere) – will change the comity between ethnic groups and jeopardize the revival. How will it play out if thousands are thrown out of their homes? Will there be a battle for space or will coalitions develop across ethnic lines?

Wallace said that Brooklynites – with its manufacturing base largely dead and those good wages replaced by low-paying retail jobs at places like Target, and with large numbers of borough residents living below the poverty line – may find that our current good will has been floating on a sea of relative prosperity.

He ended his lecture to a sea of applause. Most of us took the elevator up to a reception on the library's second floor as Wallace talked further about Brooklyn with individual members of the audience. I marveled that somehow he'd given a talk about Brooklyn's history and future without ever uttering the words "hipsters" or "Heath Ledger."

By the window overlooking Eastern Parkway, I can see the hundred-year-old Turner Towers, where my pediatrician Dr. Stein treated me from infancy to adolescent hypochondria.

Turner Towers is now covered with the black shroud that's at last being lifted from the Williamsburgh Savings Bank Building -- I guess it's One Hanson Place now although those of us who suffered root canals and oral surgery at the hands of its former tenants still call it the Skyscraper of Pain.

I wonder if there are still doctors' offices in Turner Towers.

On my last visit before he retired, Dr. Stein gave me some kind vaccine on a Saturday morning and I called him frantically that afternoon to say that my upper arm had gotten very swollen and I needed to see him right away. He sighed and said he was finished for the day but if I could drive over fast, he'd take a look.

Dr. Stein could find no swelling and when I showed him what I meant, he laughed.

"You're flexing your triceps muscle," he said. "Have you been lifting weights?"

Embarrassed, I walked out of the office with him to our cars. He pointed to the Brooklyn Museum across the street. "You know," he said, "I've had my office here almost fifty years and I've never been in that place once."

I told him he should go there now that he was retiring.

"Maybe I will," Dr. Stein said. He lived in Marine Park, not far from my family's house.

Tama Janowitz, who kindly blurbed one of my books, lives in Turner Towers now.

Just down from Turner Towers, directly across as I look out the library meeting room's window, is the still-under-construction sleek glass of Richard Meier's new building, On Prospect Park. I wonder what kind of people will be able to afford to live there and what their role will be in the future of Brooklyn.

Then I leave the library and hop on a passing Flatbush Avenue bus going downtown.

This was posted to

Richard Grayson's MySpace blog on Friday, September 21, 2007:

Thursday Evening at the Bowery Poetry Club: George Wallace Presents The Beat Hour

Last evening at 6:30 p.m., I was one of about 35 people -- including a dear old friend and colleague, poet Linda Lerner -- at one of my favorite downtown venues for readings and performances, The Bowery Poetry Club, for an hour presented by the always-dynamic literary impresario George Wallace.

Although the scheduled bongo player was MIA, audience members improvised and there were some great sets by poets and performers:

Barbara Southard read some interesting poems, including a couple about downtown Jacksonville, a place I know well from having worked as a college instructor and run for Congress in that neighborhood;

Donald Lev, an old friend from the scene in the 1970s -- I had several stories in and was interviewed in Home Planet News, the great newsprint indie literary review founded by him and his late, much-missed, wife Enid Dame -- read some of his great film-reviews-as-poems (on The Goodbye Girl and Chalk) and other inimitable stylings by the guy who famously played The Poet in Robert Downey Sr.'s classic 1969 black comedy Putney Swope;

Brant Lyon and A.J. Antonio presented some wonderful jazz-poetry to musical accompaniment; and

Levi Asher, brains behind LitKicks and a lot else, read a couple of terrific Beat-style poems, the second a righteous riff on the Iraq war, and as a finale, brought up special guest Ed Champion, fresh from an interesting encounter with Danica McKellar, who joined Levi in a duet of simultaneous readings of a cut-up of Gregory Corso's "Bomb" to the accompaniment of an improvised bongo beat. It was a great way to end the evening, and since no Beat poetry event is complete without someone in the audience getting offended and leaving in a huff, it apparently prompted a guy in the first row to get up and go.

Snaps to everyone, especially George Wallace and the rest of the crew at the BPC.

This was posted to

Richard Grayson's MySpace blog on Friday, September 21, 2007:

I have a post up at Only the Blog Knows Brooklyn:

KLEZMER MEMORIES FROM RICHARD GRAYSON

Here's another terrific story from frequent OTBKB contributor, Richard Grayson. Read a great interview with him here.

Tonight (September 20) at Barbes, you can catch Andy Statman at the 10 p.m. show. The promo for his appearance says:

A truly extraordinary artist, Andy Statman began his career in the 70's as a virtuoso Mandolinist who studied and performed David Grisman, went on to study clarinet the legendary Dave Tarras and became one of the main architect of a Klezmer revival which started out 30 years ago and has since informed and influenced folk, Jazz and improvised music forms. Andy draws equally from hassidic melodies, folk tunes from new and old worlds alike and Albert Ayler-influenced free-improv. The result reads like a very personal search for the sacred based both on traditions and introspection.

The "legendary Dave Tarras" was my Uncle Dave, called by Wikipedia "possibly the most famous 20th century klezmer musician. . .known for his long career and his very skilled clarinet playing."

Uncle Dave and his klezmer band played at my bar mitzvah reception at the Deauville Beach Club in Sheepshead Bay back in 1964. Many years before that, he played the clarinet at the wedding of my great-grandparents back in Ukraine.

Although he was my great-great-uncle, he was only 53 when I was born (in my family, we marry young or not at all) and was around till I was almost 40. A couple of weeks after The Village Voice gave a nice notice to my first book in 1979, Uncle Dave trumped that with a Voice cover story that called him "King Klezmer."

Married to my grandmother's Aunt Shifra, Uncle Dave came to America with my grandmother and his in-laws, my great-great-grandparents, who'd later own a candy store on Stone Avenue in Brownsville.

At Ellis Island, they fumigated his clarinet and he was forced to work for his brother-in-law, my great-grandfather, a prominent furrier who'd been in America for years, until he could pay for a new one.

When I was a kid, Uncle Dave lived on Tilden Avenue in East Flatbush, just across the street from Tilden High School (closed last June and broken up into smaller schools). At one point my mother decided I should have clarinet lessons and Uncle Dave came over and gamely tried to instruct me.

But I have no musical ability whatsoever and I hated the taste of the reed in my mouth. Although I loved Uncle Dave and wanted to please him, whatever came out of my clarinet must have sounded like a catfight.

After just a few weeks, he said, "You don't like this, do you?"

I shook my head.

"What do you like to do?"

"I don't know. . . writing?"

"Then you should write." He went downstairs and told my mother the clarinet was not for me.

Uncle Dave had come from a musical family, and his son-in-law Sammy Musiker, married to my grandmother's cousin Brauny, was an ace on both the sax and clarinet. A friend of Gene Krupa who played in Krupa's band, Sammy brought jazz and swing influences into klezmer before his untimely death.

My friend Bert Stratton, a clarinetist with the Cleveland band Yiddishe Cup, once did research at the YIVO Institute and sent me a composition of Uncle Dave's entitled "Richard's Ba Mitzva," though I'm pretty sure it was done not for me but for his grandson Richard Tarras or his grandnephew Richard Shapiro. All of us were students at Meyer Levin JHS in the early 1960s, so the title could do triple-duty.

Although Uncle Dave was well-known in musical circles – he had a weekly show on a Brooklyn-based radio station when I was a kid – mainstream recognition came with the klezmer revival late in his life. In 1984, the National Endowment for the Arts gave him a Heritage Fellowship in recognition of his contribution to traditional music.

After Aunt Shifra's death, Uncle Dave lived with a widow whose family he'd known for many years. To avoid losing social security benefits, they had only a religious marriage ceremony, not a civil one. We celebrated their "wedding" at the Shang-Chai kosher Chinese restaurant on Flatbush Avenue.

The last time I saw Uncle Dave, he gave me a gift: a signed copy of an LP by Enrico Caruso. I still treasure it.

Uncle Dave died at 95 and is buried next to Aunt Shifra in the family plot at Old Montefiore Cemetery in Springfield Gardens. A musical staff adorns their headstone.

Andy Statman is carrying on and extending the traditions of klezmer music. Catch him if you can.

This post appeared on

Richard Grayson's MySpace Blog on Monday, September 17, 2007:

Sunday at the Brooklyn Book Festival: Why Book Reviews Matter

The last of four panels in the National Book Critics Circle's event "The Age of Infinite Margins: Book Critics Face the 21st Century," took place yesterday at the Brooklyn Book Festival. At 1 p.m. over a hundred people gathered at the Brooklyn Historical Society to attend the panel, "Why Book Reviews Matter: How We Decide What to Read (Next)."

Deborah Schwartz, the president of the Brooklyn Historical Society, began by welcoming us to their building. I've been there a number of times, and they always seem to have great exhibits of photos and other stuff from the old days, most of which I was around to see (trolleys, Ebbets Field, pterodactyls over Flatbush, etc.).

Deborah then introduced Jane Ciabattari, NBCC board member, short story writer, book critic and presence on the NBCC blog Critical Mass, today's moderator, who in turn introduced the four panelists:

Colin Harrison, author of five novels and vice president and senior editor at Scribner's, a resident of Brooklyn;

Kathryn Harrison, author of novels as well as a memoir, a biography and an essay collection, also a Brooklyn resident (you figure it out);

John Reed, novelist and books editor of The Brooklyn Rail (his residence was left unspecified); and

Harvey Shapiro, poet, former editor of The New York Times Book Review, a resident of Brooklyn Heights for 50 years.

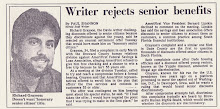

(Full disclosure: When my first book was published in 1979, I placed a copy with a cordial note on the doorstep of Mr. Shapiro's brownstone. This friendly gesture did not get that book reviewed in the New York Times Book Review, but Mr. Shapiro did allow a mildly favorable review of my third book to appear in the NYTBR in August 1983; three weeks later he was replaced as editor by Mitchel Levitas).

Jane's first question for the panel: How do they decide what to read next?

Colin said that as an editor at a major publishing house, a river of paper comes to his desk every day. If the book is from an agent or an editor that he knows or on a topic that interests him, it has a better chance of getting his attention. Because he reads so many manuscripts, he has very little time to read for fun – and when he does so, it's usually as a "vacation" from his usual fare: a novel from the 1950s or a strange book of nonfiction.

The truth is, Colin said, he doesn't read based on book reviews. He's currently reading a Peter Blauner thriller set in New York City.

Kathryn said the last novel she read had been recommended by a student. Most books she reads are recommended by her friends, though she does look through The New York Times Book Review and the daily reviews in The New York Times.

Kathryn said there are certain writers she follows and will read all of their books. She gets a lot of books, though not as many as Colin. A lot of her reading is research for her own books. For fun, she reads Victorian novels such as those by Dickens or Madame Bovary (which she re-reads every year).

Colin interrupted to say that she reads books about serial murders, and Kathryn said that yes, she likes true crime books.

John said he finds books a lot of different ways: review copies to The Brooklyn Rail, book reviews he reads, websites he looks at, recommendations from friends. At the book festival today he'd already bought "too many books." He especially looks for books published by presses that he respects. For research, he reads strange stuff, like books on 1850s pottery. For fun, he reads things like graphic novels.

John said he wants to have The Brooklyn Rail review books early, so he relies a lot on publishers' catalogs. While a lot of review copies come to the Rail offices, he's not physically there and so doesn't see them all. Finally, reviewers sometimes come to him with books they are interested in reading.

Harvey said that there are so many books in his apartment that he has never read that he always has a huge pile of books to get to. He doesn't really use reviews as a consumer guide; rather, he listens to friends. However, he is affected by reviews – such as when everyone suddenly "discovers" a writer like Cormac McCarthy.

Harvey also follows specific reviewers like Louis Menand and Diane Johnson: "I'll read whatever they're reviewing." He also likes Adam Kirsch's reviews in The New York Sun and Charles Simic's poetry reviews in The New York Review of Books. Publications he reads include The New York Times Book Review, New York Review of Books, Times Literary Supplement, Brooklyn Rail and the newsletter of the St. Marks Poetry Project, which is important for reviews of poetry books.

Jane then asked the panel how they want word to get out about the new books they themselves have coming out and what the ideal in terms of book reviews would look like.

Harvey said that it is imperative that advance copies get to the following periodicals well in advance: Publishers Weekly, Library Journal and Booklist (the latter is especially important for poetry, since a good review will create library sales).

Review outlets that help sell books, Harvey said, are The New York Review of Books, New York Times Book Review, Talisman, literary magazines, The Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times Book Review (although he got an unfortunate review there) and Boston Review.

John agreed with Harvey's response but said that even if you get a lot of reviews, a lot of other things have to happen to achieve maximum sales. He noted that publishers often mess up when it comes to advance review copies; they have to be in six months in advance. Too many people chase reviews when it's too late, like two months after publication.

John said it's necessary for books to go after very specific markets and that it's important for authors to use social networking sites, blogs, and other outlets besides the traditional print review publications.

Jane mentioned the posts about the NBCC campaign to save newspaper book reviews on its Critical Mass blog. A Harper Perennial editor said on the blog that authors definitely need a MySpace page. Another site the editor mentioned is Powells Books, which has a review of the day and with whom Harper Perennial partnered to make a film about the novel On Chesil Beach.

Jane asked Kathryn if things are done differently to get reviews and publicity for her fiction and nonfiction books. Kathryn said that it's hard to address the difference between two, that there's not much crossover in terms of readers.

Kathryn said that every book is like reinventing the wheel, even if they are from the same author; it's always like starting over unless you become one of those rare "brand names" like Stephen King. Selling books is not like selling toothpaste, as publishers say, in that books are not necessities.

Kathryn's preference is to be completely involved in something else during the publicity process; in some ways it helps to let go of a book already published, if not thinking about it as a failure before the fact.

Jane asked her about blog tours, about guest-hosting on blogs – something authors are beginning to do; Kathryn said she would certainly do that, as she would anything helpful for her books. She has a website and will probably get a MySpace page, though she called herself "an Amazon virgin" who has never checked her sales rankings or the reviews of her books by readers there.

Colin said that word of mouth is the best way to sell books. As an editor, his perspective is that the publishing company will work hard to get authors reviews. Unfortunately, due to factors beyond their control, publishers do something send out galleys late.

As reviews come in, things happen to books; sometimes a book you had high hopes for garners poor reviews that can be devastating to authors. As an editor, Colin said, he tells his authors that this is just the immediate response but the reviews are not everything in terms of success.

Right now, Colin said, there really isn't the reviewing culture that existed in the past. While professional critics are often very good, a number of book reviews today are done by occasional reviewers who freelance and these reviews are not always the best; sometimes it's easy to tell that the reviewer hasn't really read the book but based his review on the press materials.

Colin said the good reviews are sometimes not as intelligent as bad reviews because lazy reviewers who don't read carefully are loath to expose their failings with a bad review and so indulge in mindless praise.

Sometimes, Colin went on, a single review can have an electrifying effect that creates a chain of critical awareness and set the perception of the book. And some books get reviewed very well, but they don't sell many copies anyway. Few newspapers do daily reviews anymore.

Colin mentioned a book he edited, the first novel by Anthony Swofford, whose memoir Jarhead sold well after magnificent reviews. The novel got a "murderous" review in The New York Times Book Review, and although that was really the only poor review the book got, it set the perception for the novel, much to the detriment of its sales figures.

Colin repeated what others said, that there's a very short period of time in which responses to a book come in and actually matter; most books are in the marketplace of ideas for only a brief moment. A lack of reviews can be very discouraging to writers.

With newspaper reviews in decline, outlets like The Village Voice's Voice Literary Supplement gone, things are much harder, but Colin hopes were merely in a pause in the critical culture; he expects more reviews from newspapers will migrate from the print edition to the online one. There are some wonderful literary blogs that do a good job; he mentioned Jessa Crispin's Bookslut, Maud Newton and Lizzie Skurnick's The Old Hag, among others.

John took up the question and said his magazine likes to champion underdogs, so he particularly looks at small presses, of which there are many excellent ones that bring out books that might otherwise slip through the cracks. The Brooklyn Rail has a political bent and that affects its book coverage. They try to review books that they can help, which is why they rarely review books long after publication, except to right what he feels is an unjustified neglect by other review outlets.

John said a lot of an author's best coverage comes off the book pages, where the author can better define and control the coverage to her advantage.

Again, John mentioned social networking sites like MySpace, saying writers take to them like a duck takes to water. Authors who are afraid of these sites must dive in, because they will inevitably become more important.

Harvey began by saying that in his lifetime, middlebrow culture has completely disappeared. At one time magazines like Life, Time and Newsweek would feature authors on their covers because books were an important part of American novel.

[My intrusion: As a kid in the 1960s, I used to collect autographed Time covers, and in my collection are those of a number of novelists, such as John Updike, who made Time's cover when Couples came out. Updike signed it, "I'm glad you liked Irene," referring to the character of Irene Saltz, whom I told him I thought was the most well-drawn.]

Harvey said book culture receded in importance as the boundaries broke down between highbrow and lowbrow culture, with middlebrow culture completely disappearing as postmodernism reigned. This was in many ways a good thing, but it ended mainstream coverage of literary works in the mass media.

Today, because of financial problems unrelated to books and book culture, newspapers are cutting back reviews. To some degree, Harvey said, editorial space is determined by the amount of advertising in a section.

When he was editor of The New York Times Book Review, a company vice president once told him that it was okay for the section to lose two million dollars a year but if it lost three million, they'd be in trouble. No one ever gave him a balance sheet although at one point an executive told him the section was actually running int the black.

Harvey said that under him, the section reviewed about 6% of reviewable books, not including very specialized titles for a narrow audience. At one time he wanted to eliminate all art and graphics to make more room for book reviews, but of course that never happened. He thought the extra space could be given over to more review content.

The sad truth, Harvey said, is that book publishers don't advertise much. The inability to financially support itself is why The Los Angeles Times Book Review ceased to exist as a separate section as was folded into an insert in the Arts section of the paper.

Interestingly, Harvey said The New York Times Book Review began as part of the Arts section of the paper and then he mused, "Who knows, it may eventually go back to that."

Jane said the panel was running out of time and she wanted to mention some other kinds of publicity of books: Oprah Winfrey and her book club on her television show, for example, really did bring mainstream attention to a literary novelist like Cormac McCarthy when Oprah selected The Road.

After asking if anyone in the audience relied on The Colbert Report as a source of information about books they might read (no one did, apparently), Jane asked the audience members what other sources they did get information about books from.

Here are some responses people called out: page one of The Wall Street Journal, Booklist, Publishers Weekly, Kirkus Reviews, The Leonard Lopate Show and The Brian Lehrer Show on public radio station WNYC, critic James Wood (now at The New Yorker), Salon.com, Rain Taxi, American Book Review (particularly important for poetry), Booklust.com, Amazon.com reviews (John Reed said Amazon has been culling and deleting some reviews and reminded everyone that books are reviewed there by people who also review soap) and various literary blogs.

The Brooklyn Book Festival people had another event scheduled at 2 p.m., so Jane thanked the panelists and the audience and wrapped up an interesting series of panels from the National Book Critics Circle.

This post is from

Richard Grayson's MySpace blog for Saturday, September 15, 2007:

Friday Afternoon at Housing Works Books Cafe: "Grub Street 2.0: The Future of Book Coverage"

Yesterday at 4:30 p.m. I was in a very large crowd, perhaps 65 people, filling the Housing Works Used Books Cafe to attend the National Book Critics Circle's second of four panels in their series "The Age of Infinite Margins: Book Critics Face the 21st Century."

Entitled "Grub Street 2.0: The Future of Book Coverage," it was moderated by John Freeman, the widely-published book critic and president of the NBCC, who began by saying it was great to see that so many people left work early to come.

He thanked Scott McNemee for the title of this session, which of course comes from Samuel Johnson, who lived on Grub Street and who popularized the term as one for hack writers when his dictionary called it "originally the name of a street...much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries, and temporary poems, whence any mean production is called grubstreet."

Mentioning George Gissing's novel New Grub Street, set in late-19th-century London—which contrasts a pragmatic journalist with an impoverished writer and examines the tension between commerce and art in the literary world—John noted that although the current climate for book reviews was considered bad, things may have always seemed bleak. He quoted from Gissing back in 1891:

Presently the conversation turned to periodicals, and the three men were unanimous in an opinion that no existing monthly or quarterly could be considered as representing the best literary opinion.

'We want,' remarked Mr Quarmby, 'we want a monthly review which shall deal exclusively with literature. The Fortnightly, the Contemporary -- they are very well in their way, but then they are mere miscellanies. You will find one solid literary article amid a confused mass of politics and economics and general clap-trap.'

'Articles on the currency and railway statistics and views of evolution,' said Mr Hinks, with a look as if something were grating between his teeth.

John then said things were no different in 1959, when Elizabeth Hardwick wrote her scathing Harper's essay, "The Decline of Book Reviewing," which lacerated the turgid state of American book reviews:

In America, now...a genius may indeed go to his grave unread, but he will hardly have gone to it unpraised. Sweet, bland commendations fall everywhere upon the scene; a universal, if somewhat lobotomized, accommodation reigns. Everyone is found to have 'filled a need,' and is to be 'thanked' for something and to be excused for 'minor faults in an otherwise excellent work.'

After briefly discussing the NBCC's current campaign to save newspaper book review sections, John introduced the panel:

Melissa Egan, producer of The Leonard Lopate Show on New York's public radio station WNYC;

Dwight Garner, senior editor of The New York Times Book Review and writer of its best-seller list column and its Paper Cuts blog;

Emily Lazar, producer of Comedy Central's The Colbert Report;

Jennifer Szalai, senior editor at Harper's magazine;

Erica Wagner, literary editor of The Times (London); and

Steve Wasserman, former editor of The Los Angeles Times Book Review, currently a literary agent and the incoming editor at Truthdig.com, author of the recent Columbia Journalism Review article on the decline of book coverage, "Goodbye to All That."

John began by asking Erica about the literary situation in England and if newspaper book sections are livelier there.

Erica said the crucial difference between our countries is that England is much smaller and still has national newspapers that have a greater influence over literary culture. At times, that can create an insular literary culture, "as if we are all in conversation with ourselves" and outsiders may feel excluded.

The British literary community knows each other well, Erica said, and are not as dispersed as in the U.S. so that when, say, a new Philip Roth novel comes out, people compete with each other to be the first to review it.

Erica's newspaper, The Times (as opposed to the separate entity The Sunday Times), never had a stand-alone book review section until she started one in 2005. The section is 20 pages, with games and crossword puzzles in the back. She's trying to reach people who ordinarily don't read book sections.

British newspapers also sponsor literary festivals, as hers does the Cheltenham Festival of Literature, which takes place in early October. The Times provides financial support for the festival and has a say in programming, which it ties to coverage of the event. Her book section the Saturday before the festival will be all about it and other sections of the newspaper, such as the arts section, will cover other aspects of Cheltenham's guest authors. The sponsorship has proven to be a good value all around.

John said that this reminded him that authors today can't hide from the public until they've developed a loyal cult following. Before that, they have to be out on tour, plugging the book as much as they can. He asked Emily how she chooses authors to appear on Stephen Colbert's show.

Emily said they viewed the show's primary obligation to be one of entertainment; it's not a book review show, but books are a great resource for them. They rely on book reviews to help select author guests from the many books that they get (about 60-80 each day).

Of course the premise of the show is that the Colbert character never reads any of the books he's interviewing the authors about. They would rarely have a novelist on, as the audience (and Colbert) need to understand the idea of the book right off the bat. Novels usually don't have clear arguments and their show isn't about stories. They are looking for books, essentially, that contain arguments that can easily be made fun of.

While Salman Rushdie did appear recently on Colbert, it wasn't for any of his novels. They also had a recent appearance by Garrison Keillor, but he is less a literary writer to them than the apotheosis of NPR banjo-playing folksiness, something that can be satirized.

John noted that much of the news about the Bush administration, including revelations seen nowhere else, have come not from newspaper or magazine journalists but from the authors of books. He asked Steve, now at Truthdig.com as opposed to the Los Angeles Times Book Review, about the differences between reviewing books about current events on the Web and general book reviewing in newspapers.

Steve said that the fact that newspapers have to rely on books for news about the Bush administration testifies to newspaper journalists' total abdication of their responsibility to search for the truth. As for technological change, it may make communication more swift, the human desire to make sense of our world and seek answers remains the same.

He looks for the same qualities in all reviews: the degree to which the writer is accurate and composes with style and grace and has something interesting to say. He thinks victory will ultimately go to those blogs and older forms that have these qualities in abundance.

Steve said that the proliferation of blogs and other new forms still hasn't shown that they can produce an economic model for employment of people to write about books. Zealots in their garages now can post their manifestos on the Internet without first going through a discriminating filter that editors provide.

John then turned to Dwight and asked him about his blog for The New York Times. Dwight said that blogging is sticking a live wire into one's neck. At the book review section, they don't really have much contact with readers except for the relatively few letters that come in, but when he posts something on his blog, people respond immediately. That people online are "always yapping" means that the blogger has something like a pet that constantly craves attention and it's difficult to keep up.

Dwight likened book reviews to restaurants, while blogs are more like good hot dog stands, a fun place to go for a quick bite.

John asked Jennifer about her magazine's use of long-form reviews. In view of the widely-assumed decline of people's attention spans, has Harper's thought about changing this format and going to shorter reviews?

Jennifer said that the magazines had no plans for shorter reviews, that they and their readers seemed to appreciate the 4,000-word reviews they run or John Leonard's 2,000-word columns covering a number of books. As far as shorter attention spans go, Harper's appeals to readers curious about the world around them, people who like the long form. A not-for-profit organization, her magazine doesn't have to worry so much about economic imperatives.

John turned to Melissa and said that Leonard Lopate's radio show had the same instant feedback as blogs. He asked how she finds the authors to appear on the program.

Melissa said she usually goes by her gut feelings about the book; if they like a book, they invite the author on without worrying that she might be boring. Some people are amazingly good writers but find it hard to communicate over the air. Leonard Lopate's job is to pull them out. Their show does loads of first novels, often before there are many reviews out of these books.

John asked if she ends up reading a lot of stuff, and she said they do aggressive screening since they get 40-60 books a day. They have to do a lot of skimming.

John then discussed all the multimedia add-ons newspaper book sections now contain: the podcasts, Q & A's, etc. He asked Erica about these in both her paper's print and online book sections.

Erica said we are trying to do more and more multimedia, but nobody really yet knows what the effect of these add-ons will be and if the expenditures made will be worthwhile. After all, if they decide to do a podcast, someone has to be the interviewer. They are basically throwing stuff out and seeing what sticks, but none of this material comes without costs. The current confusion about all this comes down to economic reality.

John asked Dwight if the New York Times is also heading in that direction, and he pretty much echoed Erica in saying they were throwing everything out at readers online in particular and are waiting to see what works. For him, blogs and podcasts are not as much fun as book reviews themselves.

John noted that there were fewer newspaper reviews, and while there were many blogs, blogs don't have editors. He asked Steve about this: are we losing the kind of incisive criticism a Susan Sontag-type review once provided.

Steve said newspapers and all mass media worry about the need to "retain eyeballs" and so they can neglect the pure mission of providing criticism. Many book review outlets have blurred the boundary from being critics to being spin doctors for authors or publicists for book publishers.

In a furiously visual culture, Steve went on, mass media depend upon "a certain velocity of image." He views books as the most pure form and hates interviewers who ask authors, "What more can you tell us about your book?" An honest author might answer, "I spent three years writing my book and put everything in in. If you want to know that, just read my book. It says everything I have to say."

All podcasts, Q & A's and the other add-ons are a species of higher gossip, Steve said, a kind of Rope-a-Dope or junk food, to bring in the kind of person who normally doesn't go near straight book reviews. But they have little nutritive value compared to the work itself, and the work should be the primary focus.

John quoted Updike when he said that the perfect book review would quote the book under discussion in its entirety.

Then John asked Emily about the relentless plugging of books and whether Colbert satirizes that in his author interviews, making fun of the current system of book publicity.

Emily said the Colbert persona is so misinformed, his guests have to constantly correct him about his assumptions regarding their books. Keep in mind that their show's demographics skew toward very young viewers who probably read fewer books. If they were more conventional in their author interviews, their audience would get turned off.

She said Colbert can sell books that no one else is paying attention to. At work she has to deal with books in a "circus atmosphere," but at home, as a reader, she wishes her work self didn't have to resort to these circus tricks to bring attention to books.

John noted the paradox that while technology is making it easier to publish, it's also making it harder to find time to read. He then turned to Melissa and asked how she gets listeners to the radio show involved when so much else is competing for their attention.

Melissa said the show asks for the listeners' direct involvement, and uses it, in the form of email questions and comments to Leonard Lopate during the show; he incorporates these into his interviews with guests and also takes phone calls from listeners, who can talk to the authors who are guests.

The radio show also has contests, such as a recipe swap, and it recently had a contest for drawings using googly eyes in connection with a new book by Amy Sedaris; the contests often draw as many as 400 entries from all over the country.

John said that Steve Wasserman was a recent guest, discussing the decline of book reviewing, and he noted that soon after the interview, it could be downloaded and streamed online and that people could post comments about the show.

Melissa said that people suggest ideas for segments and guests constantly, that they use many of these ideas but only if they agree they are worthwhile.

John asked Jennifer if young reviewers, who grew up in a different mass media environment, write differently than old-time critics like Irving Howe. She said every generation takes a somewhat different approach, but young Harper's contributors are also their readers and are comfortable with the long form; reviewers in their twenties for them are happy to write 4,000-word reviews. While most twentysomethings may have a different attitude toward reading than people in their twenties did forty years ago, that's not true of the young reviewers Harper's publishes.

John turned to Dwight and asked about the Times Book Review, noting that many older book reviews the paper had in their online archives, unless they were by critics like Helene Vendler or Edward Hirsch, were often quite badly written in comparison with today's reviews.

Dwight said that he's pleased when he can go back and find reviews of old stuff, like John Gardner novels, that still stand up, but he agreed they have higher standards today. Back in the day, when he was coming up, young book reviewers could hone their craft in alternative weeklies, which have drastically cut or eliminated book coverage by now. Blogs, with a lack of editors, don't help a writer develop in the same way.

Steve Wasserman said that he doesn't understand then why the chain bookstores and some others seem to have tons of literary quarterlies. Even if these are subsidized and read by only fifty people, can't talented writers get their start there? All the quarterlies actually seem desperate to find fresh, excellent material, so talented young writers still can get published today.

Steve mentioned a UCLA student who a few years ago approached him after a panel like the one today who asked if he would look at her stuff. He did and liked it, and Cristina Nehring has gone on to produce superb work for Harper's and other magazines and has a book contract with HarperCollins. Of course, not all people with literary aspirations have as much talent as she does, and they will not succeed, and that's a good thing.

Steve affirmed that there were lots of outlets for writers with talent although he admitted they pay abysmally. Erica said she would agree, though England is a more closed world and sometimes she gets people writing her saying the British literary world is a kind of conspiracy to keep certain people down. She wishes she had more space to publish more writers who can genuinely contribute to the literary discussion.

John stated that novelist and poets write for their own enjoyment and don't feel terrible if their stuff doesn't get published, but nobody sits home and writes book reviews for their own pleasure. Without enough outlets, potential book reviewers are frustrated.

John said this frustration leads to the acerbic quality of some, but not all, literary blogs, who feel they must shout out to get heard. Some have compared them to the English essays of the eighteenth century who were similarly acerbic. Is this an apt comparison?

Steve said that at the risk of psychoanalyzing anyone's rage, he believed it was better that these people get their anger out with words on their blogs rather than climb up to a tower and start shooting people willy-nilly. Their rage is a perverse acknowledgement of how deep people's feelings about literature are.

What he dislikes about the Internet is that its neat aesthetics confer an unearned authority on the scribblings of ranters. You used to be able to tell a "nutter" by the bizarre formatting of addressing on their envelopes, their disregard for margins, their crazy scrawl. It was so much easier in the old days to spot an unhinged person. Now the Internet makes it harder to tell; all opinions, at first glance, appear equal. This is terrifying, so you've got to read online stuff carefully.

John asked Dwight how he reads the Internet, and Dwight said that at the Times Book Review, they don't really look to litblogs for literary criticism but for news of the publishing world and gossip. To look at literary criticism, they search the online book sections of other newspapers like The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, etc. Although they don't provide real literary criticism, Dwight said, blogs do have the virtue of distinctive voices.

John said that the NBCC blog Critical Mass can get famous writers to send them articles without paying them – a somewhat depressing situation if you think about it – but people don't read them, like a great essay Richard Powers did for them. Most of the traffic to the organization's blog comes from some link by another site, like Arts and Letters Daily.

Jennifer said she looks at litblogs for news as well, but she might not want online criticism because she herself is not used to reading long pieces on the Internet. Probably young people feel differently. She uses the Web to "get a sense of what's out there." But there's a lot of glut, and sometimes good things are hard to find.

Emily said some of the reviews of her husband Jonathan Alter's book seemed so petty. When reviewers aren't thoughtful, they lose credibility. She noted that some reviewers discredit an entire book because an author got one or two facts wrong. Then she said she was speaking more as the wife of an author than a TV producer.

Jennifer said there are real problems with book reviewers who want to feel superior to the books they are assigned.

When Emily said snark is more entertaining, Jennifer said that reviewers must communicate their critical experience in encountering work. It's bad to be condescending to the books under review; particularly with fiction, reviewers need to have a little bit of humility. Being a showoff results in the worst reviews, and editors need to guard against letting condescension creep into their publications' reviews.

Emily said she wanted a review of a book that was written, not the book the reviewer thought ought to have been written. Dwight said he was a fan of Emily's husband Jonathan Alter's writing and said that his columns are tough, and so he should expect tough reviews of his own work.

John asked Dwight if they often had to kill poorly-written reviews. Dwight said they rarely do this; instead they try to fix it. It looks bad if the Times Book Review kills a review because it seems as if they are favoring a writer and don't want her to receive negative criticism. They hate cheap shots, but some hits and fair hits.

Steve said that to him, a worse sin is the widespread prevalence of indifference in book reviews. "I'd embrace a crime of passion, however wrongly directed," he said, "over the indifferent complacency I see in many reviews."

Steve said he wanted to feel a presiding sensibility informing a book review, a sense that the reviewer holds readers in high regard and understands the high stakes of a review. He wants reviews that embrace the strange, the unknown, even the perverse – writing like that would go a long way toward gaining eyeballs for book review sections.

John asked Melissa if discussions on the Leonard Lopate radio show ever get combative or confrontational, and she replied that emotions are sometimes important, though if you're interviewing Henry Kissinger, you must approach him with respect. They try to have on only people that Leonard respects, and if the conversation gets heated, that's fine.

John then turned to Emily and asked her role in scripting the interviews; if they've got on a Swedish writer with a skeptical view of global warming as they did recently, what's their strategy to make the interview entertaining?

Emily said lots of writers make good foils for Steve's Colbert character, and it's Steve who usually figures out how. She couldn't do it for Keillor and would have passed on him as a guest, but Steve said he'd out-folksy him. Steve loves the challenge of interviewing guests his character would really have nothing to say so. The more difficult the interview, the better Steve likes it.

John said they were nearing the end of the hour session and asked each panel member what they were currently reading. Some of their answers:

Emily: Philip Roth's The Counterlife

Steve: Naomi Klein's The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism ("be very scared")

Melissa: Akiko Busch's Nine Ways to Cross a River: Midstream Reflections on Swimming and Getting There from Here

Erica: Carol Gould's Spitfire Girls: A Tale of the Lives and Loves, Achievements and Heroism of the Women ATA Pilots in World War II

Dwight: Phoebe Damrosch's Service Included: Four-Star Secrets of an Eavesdropping Waiter

Jennifer: Gyula Kruda's Sunflower

With that, John closed the session by thanking the panel and the audience, reminding them that at 5:45 p.m., there would be another panel, "What We Talk About When We Talk About Books: Can Criticism and Promotion Coexist Today?"

Unfortunately, someone's grandmother was waiting for me at Sal's Pizzeria in Williamsburg and so I could not stay for it.

This was posted to

Richard Grayson's MySpace blog on Friday, September 14, 2007:

Thursday Evening at Housing Works Bookstore Café: “Literary Magazines Go Electronic”

Last evening at the cozy Housing Works Bookstore Café in Soho, I was one of about two dozen people in a mostly older crowd in the audience for the initial panel in the National Book Critics Circle series, "The Age of Infinite Margins: Book Critics Face the 21st Century." This panel was "Literary Magazines Go Electronic: Where's the Print Edition in the Library?"

First a staff member explained that Housing Works is a community-based, not-for-profit corporation providing housing, health care, advocacy, job training, and vital supportive services to homeless New Yorkers living with HIV and AIDS, and she discussed the workings and activities of the Used Bookstore Cafe; for me, it's always been a wonderful place to visit.

Then the panel's moderator, Barbara Hoffert of Library Journal, an NBCC board member, was introduced.

Barbara, who got to stand at a podium with two rather rickety-looking raised platforms on either side of her, asked the panelists to take their seats and then introduced them. From the audience's left to right, they were:

Brigid Hughes, editor of A Public Space;

Karen Gisonny, Helen Bernstein Librarian for Periodicals and Journals at the New York Public Library;

Jeffrey Lependorf, executive director of the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses;

D.T. Max, author and former New York Observer book columnist;

Kevin Prufer, poet, NBCC board member, and editor of the literary magazine Pleiades;

Scott McLemee, columnist at Inside Higher Ed columnist and award-winning critic; and

Susan Thomas, Assistant Professor/Evening and Weekend Librarian, Philip Randolph Memorial Library, Borough of Manhattan Community College (where I'd be teaching this morning if not for the Rosh Hashanah holiday).

Barbara began the discussion by going to Kevin's article in which he described how he'd hoped to spend an afternoon at the University of Central Missouri's library catching up on his reading of literary magazines such as Virginia Quarterly Review, only to find that the library had canceled all print subscriptions and he was directed to get the journals on the online database. Barbara noted that this will be the "flip year" for many academic libraries – the year the majority of their holdings will become electronic rather than print-based. Serials (periodicals) are, of course, much more likely to be in digital form than books.

Barbara's first question for the panel was whether the electronic reading experience is measurably different than the print reading experience. Kevin said the obvious difference in terms of literary magazines is that they are edited lovingly and carefully, not just the content of the texts (stories, poems, essays) but also the layout: both the look of each page and how the contents are placed so that reading the journal from poem to story to poem, etc., is a continuous aesthetic experience – that is lost when the material is transferred to digital form.

A second issue is that the majority of book reviews of small press books, particularly poetry, appear in literary magazines, and readers will look through the latest issues to see what books are being published – something they're far less likely to do when the current reviews are available only electronically.

A third issue, Kevin continued, is that some writers refuse to give electronic rights to their works, so that a magazine's story by such a writer (Brigid Hughes gave Nadine Gorimer as an example) will not appear in the digital version, only in the print one.

Karen noted that people love to browse through new issues cover to cover, looking the ads and graphics that are lost electronically.

Jeffrey said online reading is simply harder; in addition, literary magazines – unlike research-centered academic journals – are a "curatorial experience." The only advantage electronic forms may have is in presenting the moving image, joking that can be gotten from print only accidentally when a reader is drunk.

Scott, who said that for the last two years he's written exclusively for online publications, said that while we may revere old literary magazines like Partisan Review, often the print artifact of journals isn't really necessary. An advantage to electronic text is that it is much less expensive since the cost of storage and upkeep is negligible if it even exists. Distribution is not a problem as it is with print publications. The old quarterlies relied on more expensive library subscriptions (sometimes several times the price of individual subscriptions), but in an age of shrinking library and academic budgets, when storage and shelf space is finite, electronic forms have a crucial advantage.

Jeffrey noted that literary magazines often have distribution problems, and just a few weeks ago, the leading distributor of literary magazines went out of business. Newsstand distribution has never been a revenue-generating business for periodicals, which are out of date after 90 days at retail outlets (some, like the weekly People, go out of date sooner than that) – at which point their covers are ripped off, sent back to the publishers for credit and the rest of the magazines are thrown away.

Susan noted that older journals like Kenyon Review and Antioch Review were the most likely to be available on online databases and therefore most likely to be cut from libraries. Newer journals, such as A Public Space, not so readily available online, were more likely to be ordered in print form. At BMCC, one goal is to promote reading among our students, and having journals around – Susan mentioned the new Bronx Biannual – encouraged that. But budgets are being slashed and so academic libraries are less likely to order newer literary magazines, whose extras like DVDs, CDs and flipbooks (easily found in bookstores like St. Marks) are just not in the electronic versions if they even exist.

Jeffrey remarked that people are trained to read on pages and said the "virtual page" was different. J-Store, which electronically delivers electronic journals with the scanned print pages in their original form, is branching out from scientific and academic journals into literary magazines. But J-Store is primarily an archival enterprise, with something like a three-year window for publications, so that current issues of literary magazines would not be available that way. Karen said that J-Store was good but limited, and there are really no others doing the same thing.

Brigid distinguished between magazines on online databases and the websites of magazines like A Public Space, which can supplement the print issues with all kinds of extra features, like an interview with an author whose poems are in the print version. But when she goes to universities with MFA programs, their staff and students want the current print editions in their libraries and never ask for the electronic version.

Kevin said that after his experience at the University of Central Missouri library, he emailed a number of people for their opinions. Other small state university library staff members also noted that they carried far more electronic versions of periodicals than dead-trees ones, but editors at places like Kenyon Review worried about the loss of income from $24-a-year library subscriptions. Some magazines, like Boulevard, actually charge libraries less than they do individuals because libraries provide vast exposure.

Barbara said that at Library Journal, they thought the print and web versions of the magazine were designed to do very different things, some of which are only feasible online. Brigid said online editions were a necessity now for literary magazines, and editors in their twenties were much more comfortable with using their website versions. It is older writers and editors having trouble making the transition.

Jeffrey noted that online versions of litmags can link to other pieces by the same contributor or to their books for sale or supplement the print edition in numerous ways. Karin said that the New York Public Library is still subscribing to print issues and that many people prefer to look at text in things they can hold in their hands.

Jeffrey said that CLMP now has far more literary magazines in its database than when they began compiling it in the 1980s, that new litmags are being created all the time.

Then he brought up the issue of blogs. So much literary discussion, as well as discourse in other fields, today takes place on blogs, yet who is archiving the contents of blogs to make them available to scholars half a century from now who will undoubtedly want to look at blogs to understand the present literary scene? Karen admitted that the New York Public Library is doing nothing with blogs except reading them (mostly discussions on library blogs), that someone may need to scan them to preserve their contents.

Scott pointed to a recent study about the need to archive blogs. One problem noted is that there is such an explosion of blogs, it is hard to figure out just which blogs should be archived. Who would make these decisions? It also would be very expensive to archive blogs and probably would require some not-for-profit organization like J-Store. In addition, there are numerous intellectual property issues raised by blog archival.

Scott noted this transition to digital text is much harder for older people, that younger people are much more comfortable with screen-reading and manipulating the texts; for example, college students may download complex texts and then add notes or commentary, while older people view screen-reading as a more passive activity.

D.T. Max said that books are not good online, that there's no market for electronic books yet despite years after their introduction. In the mid-1990s he wrote an article for The Atlantic on the fate of reading in an electronic age (which, ironically, is not available online); at that point people believed the transition away from printed text would happen much faster than it actually has.

D.T. went on to say that his own book about a family with a fatal insomnia disorder is part-science and part-story. Some readers more interested in more information about prion diseases and other technical material mentioned in the book might benefit from hyperlinks that could be available if the book were online; yet those readers more interested in the narrative about the family would not.

Reading novels online, D.T. said, was just "not fun." The aesthetic experience is lost. He also wondered about the financial benefits for writers to having their work online. D.T. emphasized, though, that change is coming and this will also change the way in which writers write and what they write about. No area more than literature is more sensitive in changes in form. D.T. doesn't compose by hand anymore. Jeffrey noted that even the change from pencil to pen can change what people write. How will the transformation of text change literature?

Jeffrey said that whenever there is a middle person, like a distributor, it means less money for the creators and first publishers. J-Store is a not-for-profit outfit, and importantly, they not only scan and make available pages for electronic distribution but carefully preserve in a library the actual physical pages of each journal; this is another important part of their mission.

Jeffrey thinks things will be different in just a few years. Very thin electronic "papers" will exist and store and display text so that people are reading books and journals they can hold in their hands, something very close to what we now think of as physical pages. We should not assume that digital reading means online reading. Twenty years from now, most material will probably be read in electronic form. Just as there is moveable type, there will be "moveable print." How this will change reading is something worth considering.

Kevin said that while he's not a technophobe by any means, he still composed poetry by hand and that perhaps things will change less than we now think, just as D.T's article from a decade ago featured prognostications about electronic text which have not yet been realized.

Susan said that for her, it can be a relief not to have to read onscreen; for that reason alone, print culture should be preserved. She finds it dehumanizing when libraries require patrons to access certain material at terminals rather than giving them access to the physical objects of books and periodicals.

Jeffrey said that printed text slows us down in our reading, and with literature, especially with poetry, that can be a good thing, as literature is often savored rather than consumed in a utilitarian way as information is.

D.T. said books will eventually migrate to electronic forms. Books are esteemed as the emperors of information, the top form, above periodicals. But, D.T. said, look around at the books on the shelves here; they're not interacting with each other, the way species on remote islands in the Galapagos couldn't intermingle and so produced forms found nowhere else on earth. Electronic books would have malleable text and therefore would become more accurate and probably would be cited more. He noted that when newspaper reporters wanted to reference a book for an article they are writing, they traditionally call the author for a quotation or ask her what her book means rather than reading the book themselves; that may change when the book is available digitally.

Scott said that the tendency to skim more online or to skip around more may be beneficial, noting that many 450-page books contain only 150 worthwhile pages. The current organic structure of books will almost disappear, though. Oddly, he said, when he writes for online publications, he does so by hand.

Echoing a recent statement by Steve Wasserman, Scott said that while online publications have the ability to contain material of any length, in reality people get more impatient and don't read long stuff [my interpolation: like this blog entry?] online. It's only in print periodicals like Bookforum that Scott can publish articles of 4000 words. With the advent of all electronic text, 2000-word articles will have to merit it.

There was a discussion of paper submissions versus electronic submissions to periodicals; Jeffrey noted that most litmags now took material online, and Brigid say that she did but they ended up printing out most submissions for easier reading.

Barbara asked what can be done to prevent the disappearance of literary magazines from library shelves. Should there be sit-ins or read-ins like NBCC's effort in Atlanta to protest the dismissal of the book review editor at the Journal Constitution? Susan said that in the case of academic libraries, readers who wanted print copies should go over the head of the library directors to higher-ups who control the budgets.

Finally, Kevin noted that the University of Central Missouri library, whose lack of print journals spurred this conversation, has actually decided to go back to subscribing to the physical issues of many magazines.

I got to ask one of the few questions, addressing my query to Jeffrey. I said the titles of literary magazines I'd heard during the panel discussion were all established names that nearly everyone has heard of. Yet there are hundreds of literary magazines put out by individuals and groups all over the U.S., most getting little distribution and no library coverage whatsoever. When I was starting out publishing my stories, the only place I could find many of the little magazines that I submitted to and got published by was in the small private library of the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines, the predecessor organization of Jeffrey's Council of Literary Magazines and Presses. I spent hours there, yet had I been anywhere but New York, I would not be able to find these litmags unless I ordered copies individually. Was this discussion relevant to the vast majority of small literary periodicals?

Jeffrey said first that he was happy to announce that the CCLM/CLMP library had now been given to the New York Public Library and was in the care of Karen and her colleagues and more readily available to the public. He also said that people who wanted to see literary magazines that might be more obscure should come to the Housing Works Used Bookstore Café during June because CLMP sends over many recent issues, all of which are available for just two dollars each. Karen noted that the NYPL has about a thousand different literary magazines available in print.

After a few more questions, Barbara thanked the panelists for their thoughtful comments, the audience for its attention, and especially John Freeman and Jane Ciabattari for their work on making the evening possible.

Here is a post from

Richard Grayson's MySpace blog for Wednesday, September 12, 2007:

I write about last evening's 9/11 Memorial Service in East Williamsburg at Only the Blog Knows Brooklyn:

After spending hours watching General Petraeus and Ambassador Crocker testify before the Senate on Tuesday, I walk down Conselyea Street to Graham Avenue – the street sign here also says Via Vespucci – by the side of Ralph's Famous Ices, where a plaque honors the eleven East Williamsburg residents lost on 9/11.

By 7 p.m., eighty of us have tiny candles lit in plastic cups as a bagpiper plays "Amazing Grace." High-pitched drilling from a condo under construction a few feet away competes with the hymn until a cop goes over and temporarily halts gentrification as we sing the national anthem.

Father Tony says a prayer; we all recite the Knights of Columbus "prayer for peace" and the pledge of allegiance; two neighborhood firefighters place wreaths by the memorial as names are read; we sing "America the Beautiful." Tears come only when I notice two skinny hipsters remove their caps as they pass.

We begin our candlelight procession to church two blocks down. Most people here have lived in this neighborhood all their lives. At 56, I am one of the younger marchers.

Six years ago I was living in the small Ozarks town of Eureka Springs, Arkansas. I had no TV and my radio could get only Christian and country music stations; on one, a DJ mourned, "They were Yankees – but they were our Yankees."

But sitting in a back pew in a Brooklyn church, I find myself thinking not to that day but to another evening in church: March 2003 at St. Maurice's in Dania Beach, Florida. Father Roger had called for an interfaith prayer meeting on the eve of the Iraq war.

Everyone there was from Peace South Florida: our leader Myriam, a Colombian immigrant; an old Jewish couple from Century Village; two elderly Quebecois snowbirds; three high school students; and two others I'd seen at futile meetings and marches.

Father Roger distributed prayers from various religions he'd gotten online that afternoon. For the first time since a 1964 performance at Flatbush Park Jewish Center, I got to recite something in a house of worship. That night, through the luck of the draw, I asked for peace about ten times in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ.

On this night, after church, I go home to find C-Span still on. A senator is asking a general if we are any safer now. I take the crumpled program out from my pocket and for the first time see tonight's memorial had a theme: "Looking Back, Looking Forward."

This post is from

Richard Grayson's MySpace blog on Friday, September 7, 2007: Thursday Evening at the Union Square Barnes & Noble: Junot Diaz

I've just come from seeing Junot Diaz, probably my favorite American fiction writer under 40, at the Union Square Barnes & Noble. I would not be surprised if he is still in the store, signing books for the crowds that lined up after his reading, remarks, and the question-and-answer period. Not only is he a remarkable writer, but in person Diaz is enormously likable: completely unpretentious but self-possessed, very funny and spontaneous and also thoughtful and incredibly earnest about writing, literature and art.

When I first read his stories in The New Yorker in the mid-1990s, I was hooked by his voice and how seemless his fiction appeared. I've read his 1996 story collection Drown about seven times, and I've also taught it, the first time when I was a visiting professor of Legal Studies at Nova Southeastern University for the 1999-2000 school year. Although I mostly taught constitutional history, political and civil rights, and other legal studies subjects, I worked in the humanities division and asked to teach a section of the core curriculum called Other Voices, Other Visions: A Multicultural Perspective. I used Drown as part of what I turned into a course on then-recent American immigrant and minority literature, along with books by Sherman Alexie, Edwidge Danticat (the Haitian-American author I also adore -- and so does Diaz, who said he's read "Edwidge's new memoir" three times, although it just came out; both their books got side-by-side rave reviews from Michiko Kakutani in Tuesday's New York Times), Bharati Mukherjee, Gish Jen and others that term.

Since then I've taught the book again, as well as stories from it (including the hysterically funny and poignant "How to Date a Browngirl, Blackgirl, Whitegirl or Halfie" even to kids at Phoenix's Jess Schwartz Jewish Community High School).

All of us who loved his stories were waiting for Diaz's long-awaited novel, and now we're rewarded with what sounds like something worth the eleven year hiatus, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.

I got to Barnes and Noble by 6:25 p.m. for the 7:00 p.m. reading and already most of the 250 or so seats on the store's fourth floor had been taken. Even downstairs I could see his devoted fans looking through the books on sale, quoting passages to each other. It looked as if about 50 people were left standing behind the ropes once every folding chair in the audience was taken.

A couple of minutes before 7:00 p.m., after a B&N staff member had given us the usual drill about getting books signed, taking photos, shutting off cell phones, etc., I heard spontaneous applause, and I looked back (I was sitting on the aisle on the east side of the store) and saw Diaz walking to the front of the room. He wore a white guyabera and black jeans and was followed by (nobody seemed to mention this), Walter Moseley (in black shirt, pants and hat) and a few others.

Maria, the B&N events coordinator, said from the podium, "Junot Diaz, it's been a long, long, long time" as the applause got louder and louder. She then gave a formal introduction: born in the Dominican Republic, raised in New Jersey, his acclaimed stories and first collection, his numerous awards, and now this "novel that brought Michiko Kakutani to her knees," etc.

Diaz seemed kind of taken aback by the welcome, thanked everyone for coming, said as he walked up to the podium he'd seen "people I haven't seen in ten years and shit..."

"So how you guys doin'?" he asked. Lots of applause. "Lots of young heads here," Diaz said, and then he mentioned that the youngest was Kayla, only nine years old, daughter of his friends "who shouldn't even be here...Kayla, I'm sorry I dragged your family out and shit."

He said he'd do the standard thing: we'd hear a short reading, have a Q & A session and then get drunk: "Well, some of us will get drunk afterward."

And he began by reading a "footnote," not something by himself but by J.R.R. Tolkien ("Wish I could do a good British accent"):

'I am the Elder king: Melkor, first and mightiest of all the Valar, who was before the world, and made it. The shadow of my purpose lies upon Arda, and all that is in it bends slowly and surely to my will. But upon all whom you love my thought shall weigh as a cloud of Doom, and it shall bring them down into darkness and despair. Wherever they go, evil shall arise. Whenever they speak, their words shall bring ill counsel. Whatsoever they do shall turn against them. They shall die without hope, cursing both life and death.'

"I just wanted to hear that said aloud," Diaz said, and then mentioned that on his way to the store a street person had taught him a new word, meaning "the study of evil." He even called a friend who checked it out online, and the street dude was correct. Diaz asked if anyone in the audience knew the word. No one did.

"It's ponerology," Diaz said, then spelled it out and said it's weird that "nobody in the United States knows that goddam word, knowing how familar we are with evil."