We went to the Upper East Side Barnes & Noble tonight to hear a great "Writers on Writers" discussion, Why Russian Literature Matters, with the talented and perceptive Natasha Randall, Anya Ulinich and Keith Gessen.

The man responsible for making Russian literature matter to us was Spencer Roberts, a professor at Brooklyn College, with whom we first took for Russian 9, Russian Literature in Translation, in the spring of 1971, when we got closed out of most of the classes we wanted and settled for any course that sounded vaguely interesting.

We can still remember the excitement of reading the books on Prof. Roberts' syllabus: Pushkin's The Queen of Spades and Other Stories; Lermontov's A Hero of Our Time; Goncharov's Oblomov; Turgenev's Fathers and Sons; great stories ("The Lady with the Pet Dog," "Gooseberries," "The Darling") by Chekhov, whose plays we'd already read and seen, and Gogol ("The Overcoat," "The Nose," "Diary of a Madman" along with Dead Souls) and others; Tolstoy's Anna Karenina (we'd only seen the Greta Garbo movie); Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov; and Zamyantin's We, all of which blew our little minds.

Prof. Roberts would sometimes read stories aloud in a wonderful vibrant manner and he lectured on the course of Russian literature, so we still vaguely recall names, phrases, terms and titles like Belinsky, the superfluous man, Westerners vs. Slavophiles, poshlust, and What Is to Be Done?; he also spoke about his own experiences in the Soviet Union, and given his extremely conservative views in that radical time on college campuses, we students assumed he'd been a CIA agent stationed in Cold War Russia. And Prof. Roberts us told us to avoid at all costs reading anything translated by Constance Garnett.

In our last semester at Brooklyn College, we took Prof. Roberts for Russian 10, Dostoevsky in Translation, in which we read eleven, count 'em, eleven novels by the Russian master (our favorites included not just the big masterpieces but The Eternal Husband, The Double, and of course Notes from Underground, which we now teach), as well as a bunch of Dostoevsky's stories and nonfiction. By then we were a student representative on the curriculum committee of the BC faculty council and knew from our work there and Prof. Roberts' complaints to us that some people from the Comparative Literature Department groused that Roberts, in the Modern Languages Department, shouldn't have been teaching translated books. But we can't imagine anyone doing it better.

We were a little late for tonight's panel and noticed that Natasha Randall, translator of recent editions of We and A Hero of Our Time, had replaced the scheduled Olga Grushin. The other panelists are probably best known as acclaimed young American novelists born in Russia: the n + 1 editor Keith Gessen (All the Sad Young Literary Men, which we can attest can also be enjoyed by cheerful old unliterary men) and Anya Ulinich (the sweet and funny Petropolis). The panel's skillful moderator was the scholar Ronald Meyer, director of publications at the Harriman Institute and head of the graduate program in Russian translation at Columbia University.

Anyway, we're so out of it that we didn't even know the old Barnes & Nobles in this area had been replaced last summer with this brand-spankin'-new one with this incredible auditorium where the panel was speaking. We were late, of course, but we caught Keith and Anya on the TV monitors just outside, in corner of the store. Trying to not to be rude, we slipped into the back row near some bookstore staff and the control room. This will probably be on TV, so this post must be superfluous except for our usual boring alter kocker ramblings.

When we came in, Anya was talking about American MFA fiction and saying one reason Russian literature matters is that students in writing programs all over the place are trying to write Chekhov stories. We plead guilty, but since our MFA was awarded in 1976, the statute of limitations prevents our prosecution.

Natasha said that certainly to her as a translator, contemporary Russian literature matters as she wonders what she can bring to it that will make the works matter to Americans. She said the most frequent question she gets from laypeople (i.e., morons) like us is, "What translation should I read?" (We say stay clear of Miss Garnett and you'll be fine.) Natasha, after offhandedly zinging Pasternak as "ponderous" (we liked the movie Dr. Zhivago, seen at Canarsie's Seaview Theater during the Punic Wars), fell back on the Potter Stewart Gambit: you have to read Russian lit to understand why it matters.

Ron asked the panelists about their favorite works. Natasha said she didn't have one, it's usually the last one she's re-read, but at 16, it was Anna Karenina. (Did you - our mythical reader - ever see the BBC version from the 1970s? Poppy Dave, our adored then-girlfriend's grandfather, saw us watching it one night and said, "I love Levin," which sounded like the title of the sitcom version. We preferred that version's Karenin, played by the saturnine Eric Porter, though to us he'll always be Soames Forsyte - or maybe Professor Moriarty.) Keith recounted the classic Dostoevsky-versus-Tolstoy debate, concluding that one tasted great but the other was less filling. No, we're kidding. They're both filling.

Basically the problem is we can't read our handwriting in our little memo book. For example, we have an exclamation mark, meaning that it struck as important, next to something Anya said, but our notes appear to read "descended from chocolate." We do remember how Anya talked movingly (we're serious here) but funnily about being a teenager back in Russia and reading classic literature not realizing it was. For example, she thought Crime and Punishment was a mystery novel, like Agatha Christie's.

Keith said, and we quote our semi-legible notes here: "I don't like translations; Americans should make better cars." By this, he meant that if our own native (or immigrant) literature dealt with important stuff, we wouldn't have to import it from Russia. (But we find it's thrilling to get those foreign books that accelerate uncontrollably just when you're trying to step on the brakes.) Keith said we need an American Petrashevsky. (We thought American lit was already going around in circles.) Serially, Keith said something fairly profound: that writers explain what's really going on in such an opaque society as Russia, and here, well, we have Gawker (our example, not Keith's, though we've read about him there).

Oh, and a friend whom we forced to read this said Keith actually meant, not Mikhail Petrashevsky but Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, whose There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor's Baby Keith has translated. Okay, that makes a lot more sense, even to us.

Agreeing with Keith, Anya said that Russian people look up their writers as if they were priests (of the non-child-molesting variety, we presume). Poetry in Russia is more accessible than that of the U.S., where it can only be appreciated by academics and people appointed Poet Laureate. Anya said that Russian culture is much more direct than American culture and even ruder, something we notice every time we shop for appetizers on Brighton Beach Avenue. Anya said that Americans are too nice. (She may change her mind after this report on the panel.)

American readers expect entertainment, Keith said, and Russian writers don't labor under this pressure; Americans, he (correctly, in our view) noted, take all their cultural references from movies but Russians get their from books (because Russian movies are expensive and hard to find -- Ukrainian ones even more so).

Natasha talked the most about the history and development of Russian literature. Works in the 1700s were mostly extremely derivative of French novels and Sir Walter Scott's convoluted romances. One reason she fell in love with A Hero of Our Time (us too! we mean, we did too!) and translated it for a new audience was that it really was the first modern work of Russian literatue. (Prof. Roberts started our course with Lermontov's book.)

There was an interesting question-and-answer period. We are kind of embarrassed that we have done such a crappy job trying to say that this really, really was a good discussion that we enjoyed a lot. We don't mean to make fun of anyone here, because next to all these writers who know a lot we are an insignificant insect. (Yes, we know Kafka was Czech.) We apologize to Barnes & Noble, the panelists, and anyone reading this because, like 99% of people who come to this blog, you have seen something on Google Image Search that you want to upload to your own blog.

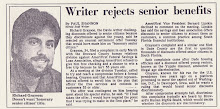

Compared to writers and scholars like Ronald Meyer, Natasha Randall, Anya Ulinich and Keith Gessen, we are just some schmuck who gives first-year college students quizzes with questions like this:

How does the Underground Man prepare for his confrontation with the officer in the park?

(A) He takes boxing lessons

(B) He buys a pair of gloves and a beaver collar

(C) He bribes a park attendant to trip the officer

(D) He compiles a list of witty retorts to use in case the officer insults him

We know we're sick and spiteful, and we despair. But in despair, as in Russian literature, there are the most intense enjoyments, and we're actually grateful to have heard such intelligent comments about Russian literature tonight. To show you (as we cannot) that the panelists (whose books you should run out and buy, they are all worth the rubles) are articulate beings, here they are in their own words:

Большое спасибо.

No comments:

Post a Comment